Longhouse Living

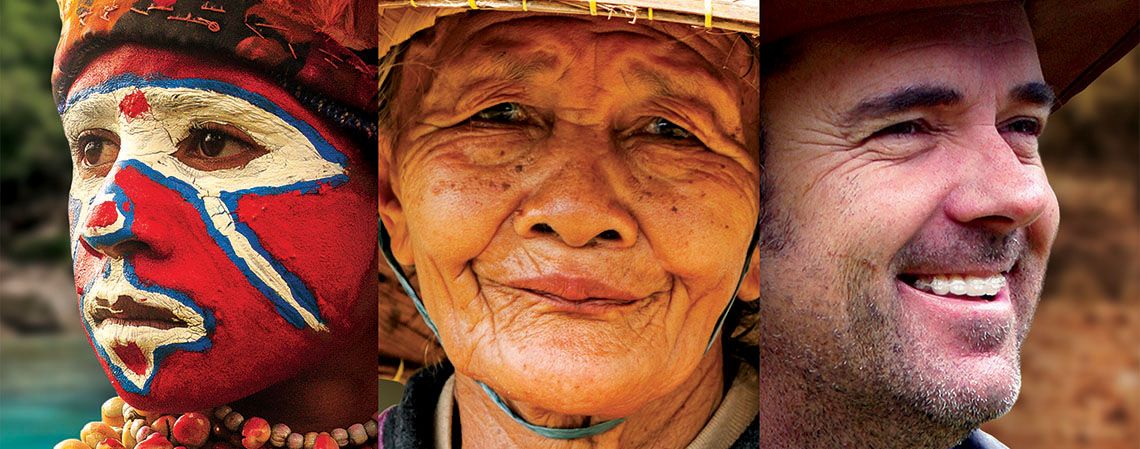

The indigenous “wild men of Borneo” are called Dayaks. They are known by the river system on which each extended family community lives. Dayaks are animistic (spirit worshippers). The Da’an lived in the center of the island. My husband Jerry always had a heart to reach the most unreached. They were known at the time to be the most treacherous, deceptive, and fearful tribe in the western half of the island. Other tribes did not visit their villages. They would give a banana as a gift in which they had planted a broken needle point. They put a piece of broken lightbulb glass in Jerry’s rice. It is probably the fact that he did not die that caused them to listen to his teaching the message of the Gospel. They tell me that today that village has a strong church.

Animists are always concerned about gaining more spiritual power. The best way to accomplish that is to take the head of a person and sever it completely while they are alive in order to capture the spirit power that person had. There are other reasons for taking heads, such as proving your manhood, which is sometimes required before marriage. Our men had tattoos on the calf of their legs as a trophy of their successfully having taken a head or two. The practice became illegal about a hundred years ago but was revived during WWII. A man pointed out a head at the top of a totem pole to me saying: “That one was made in Japan,” as he giggled. To our knowledge, only one head was taken while we lived there. It was not for ancestral reasons. The man was an outsider, a trader who stole one too many chickens and paid the price for being a thief.

Being warriors, the Dayak built their houses high up on huge stilt-like ironwood poles. Weapons were long blow guns to shoot poison darts and eight-foot-long arrows, slingshots, and, of course, their headhunting knives. Defending the village was easier from the higher elevation where they were less apt to lose a life. Our longhouse was about 25 feet off the ground, though there were people still living in sections left from the old 40-foot-high longhouse. Earlier, we had lived in a tribe where the longhouse was “50 doors” (family units). Each family was responsible for their own “home” or section of the longhouse. The Dayaks do everything as one big extended family working together, cutting down the ironwood pilings, peeling huge sections of bark off the trees for siding and interior home dividers. The floors were made of split bamboo, woven together with jungle vines.

We lived their way until we built our private house after a year when a spot was approved that was not too close to someone’s spirit bush. We dwelt among them that we might learn their language and ways to communicate the Gospel as well as learn to survive in isolation.

Our unit was about twenty by forty feet including the mud fire spot for cooking. I used the mud pad to place my two single burner kerosene stoves. We, along with our three teenage children each had two, five-gallon cookie tins for our personal items. This kept the scorpions, poisonous centipedes, and other unwanted critters out of our clothing. We had foam mattresses that we rolled out to sleep on at night and leaned against them on the floor if we tired of our cross-legged stance on the floor. That sometimes was a dangerous luxury. Our son spotted a large centipede approaching Jerry’s ear one day and yelled, “Dad, Get up quick!,” sparing him the horrible pain that accompanied such unwanted visits—speaking from experience.

After traveling all day on the river in the hot equatorial sun and moving our few things into our “home,” we were very tired. We had a house full of men come to visit us and see the strange things we brought, such as our bedrolls. They sleep on woven grass mats. Finally, one man announced, “If you would go to bed, we could go home.” We jumped up and started unrolling the foam mats to the delight of both tired villagers and our family. Our mosquito nets were our room dividers around our mats at night.

Just as Jesus left all to come and identify with us, so missionaries go and identify with those to whom God sends them to carry His message of eternal life.

Living in the longhouse provided opportunity to observe the ways of the Dayak and to show a difference in what we had come to tell them. Jerry was out of the village on a supply trip, when our next-door neighbor became sick. They called in the witch doctor to extract the evil. As I was the “village medic” I had to attend the ceremony, or I could not bring them medicine for the next week. I took the new young missionary who had recently arrived with me. The witch doctor danced and chanted and went into his trance, chewing his betelnut. He then proceeded to spit the chewed betelnut on the person’s stomach and then tried to suck the sickness out of the person, but it would not work. He tried and tried until eventually people began slowly leaving and going out to stand on the porch. I told the new missionary what was happening and said we would not leave until they asked us to go because we wanted them to understand that the power of God in us is stronger than the power of the evil one in the witch doctor. Eventually, they asked us to leave, and then they all filed back into the home and continued their ceremony.

Just as Jesus left all to come and identify with us, so missionaries go and identify with those to whom God sends them to carry His message of eternal life. Longhouse living is not for everyone. But that is what God gave us to do, and it was a privilege. Unfortunately, every missionary who has followed us has had to leave the work due to severe illness, injury, or death. Nevertheless, there are believers there today who are carrying on spreading the Gospel, and people are being saved. We were privileged to have our small part.