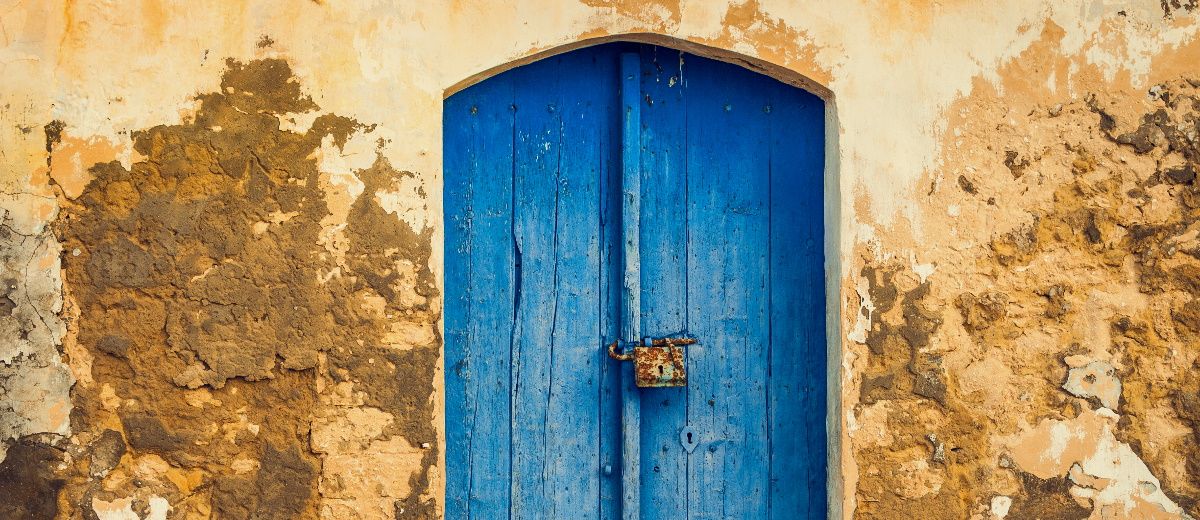

Where the Gospel is Not Welcome, Obstacles Abound

I stood inside the studio apartment, looking around at the place I would now call my home away from home, when my cell phone began to ring. Answering it, I heard the unmistakable voice of Mounir Abouda, the landlord, asking typical starter questions in Tunisian Arabic: “Labes? Chna hwalek w eddar?” This is strange, I thought. I spent a good part of the afternoon with this man — what else could he possibly want or need from me? “Aslemma khouya,” I began. “Oui, ça va bien ya sidi, kol chay labes, hamdullah.” After all, everything was perfectly fine. I was fine, the studio was fine. It had been less than thirty minutes since we parted ways … hardly enough time for my world to collapse. “Maikel,” he continued confidently. “Fama haja okhra - ghodwa lezzem temchi maia lel merkez.” Come again? Did he just say what I think he said?

He must have sensed an uncertainty in my reply when I asked him why I needed to accompany him to the police station in the morning. “Bel haqq?” I asked. No, no — he must be mistaken. I have never had to do that before. I have lived in Tunisia for more than six years and never once have I needed to go to the police station after moving into a new home. But when I brought these things to his attention, Mounir stood his ground and insisted that this was not a big deal; this was the rule and we were going to follow the rule. He made a strong point and I quickly decided to go with the flow; I agreed. “Behi, nchoufek ghodwa, Mounir. Tosbahalakhir.”

I would not say that I had the best night moving forward. That phone call ushered into my mind a seemingly endless supply of questions, doubts, and concerns. Why is this necessary? What are the police going to want to know? I have never had to do this before, but is this how it is done in the south? Why did Mounir not tell me this earlier, before I signed the contract? Is this about residency? Are the police going to require me to have residency in order to live in Medenine? Are the police going to go through my stuff and interrogate me? Does Mounir suspect me of being a missionary? Am I going to get kicked out of the country tomorrow? Will the police lock me up while they decide what to do with me? How was I able to live more than six years in the north without any police run-ins, but only one day in the south?

That phone call ushered into my mind a seemingly endless supply of questions, doubts, and concerns.

I had driven down south only days earlier in my quest to introduce the gospel to this needy area in the Muslim country of Tunisia. Most Christian activity, though minimal, happens in the northern region — primarily the capital, Tunis. Large coastal towns such as Sousse and Sfax also have a touch of Christianity, though not nearly the level found in Tunis. The question remained: Who would take the gospel to the central and southern villages and towns? I hatched a plan to set up shop in the city of Medenine, strategic because of its proximity to other places such as Tataouine, Gabes, Matmata, Kebili, Douz, Djerba, and Ben Guerdane, to name a few. I would secure housing in Medenine to have a centralized home base, and make day trips out to the neighboring towns and villages. Working with Arabic Bible Outreach Ministry online, I would receive contact information of real Tunisian people located in these towns and villages who need and want an Arabic Bible. I would set up meetings and travel to those individuals, hand out New Testaments, and attempt to start regular Bible studies. That was the plan. Little did I know how much resistance I would face along the way.

Little did I know how much resistance I would face along the way.

Finding the studio apartment on Tunisie-Annonce.com (a classified ads website), calling Mounir and setting up an appointment was relatively painless. I had been through this process more than a few times before and it was fairly straightforward. I agreed to the terms, and Mounir and I drove around town getting the paperwork and official stamps needed to complete the housing contract. Afterwards, I moved in. I was in the process of getting settled when I received the call from Mounir about visiting the police station in the morning.

The following morning, Mounir rode with me as I drove to the local police station of Medenine. I parked out front and we walked in together. We sat in the waiting area inside and greeted officer after officer. All were curious and surprised to find a westerner in the station. We waited for the police chief to usher us into his office and when he did, I found him to be friendly and courteous. Mounir told the chief about my situation, how that I had just moved into the area and taken up residence in his studio apartment not farfrom the station. We showed him the housing contract. The chief, at first, seemed like he was going to allow me to stay without issue. He mentioned that every time I would travel outside of Medenine, I would need to check into the station and inform the officers; I would also need to check in at the station every time I returned to town. I thought about it and decided I could live with that restriction. He claimed it was for my safety. Some time later, another officer came in who was extremely suspicious and upset at my arrangement. He demanded answers as to why I was trying to move to Medenine without a residency permit and what kind of business I was involved in. I noticed a change come over the chief of police and he told me that I would need to go with him the following day to the office of foreigners in another part of Medenine to ask about residency.

The next day, I went back to the police station. I picked up the chief and drove with him over to the office of foreigners. Along the way, we stopped at various checkpoints so that he could talk to other police officers and soldiers. Each one saw my face, learned my name, and greeted me. I was becoming very well known in this town and I have little doubt that I was the only westerner in all of Medenine. We made it to the office of foreigners and it was not long before the man behind the desk handed me a paper with a residency checklist. I later discovered that some of the items that were “required” to get residency were unusual and uncharacteristic of other parts of Tunisia. I knew later that afternoon that there would be no way for me to get everything necessary for residency in order to stay in Medenine. I decided my best course of action was to get out of Medenine of my own doing, instead of chancing my future to the officers in charge.

Each one saw my face, learned my name, and greeted me.

I went to sleep that night knowing that in the morning, I would pack up all my belongings and leave town. The morning came; I was pleased that it was a Sunday because I knew that fewer officers would be working that day and it would be easier for me to slip out of town unnoticed. I emptied the studio, loaded my vehicle, and drove to the center of town to find Mounir and tell him my decision. I met him on the side of the road and handed him three month’s rent in order to break the contract. I explained that there was no way for me to get residency at this time and that I was going to leave town before it became more of an issue. I said thank you and goodbye, and headed out of the very town I had previously thought would be my home. It was a strange feeling leaving town, feeling like I was running from the authorities. Every police checkpoint on my way to Gabes had me wondering if they would identify me and pull me over; it never happened. I spent the night in Gabes and then made my way over to the island of Djerba, where I spent the remainder of my time. Even with this radical change of plans, I was still able to accomplish my goal of traveling to Tunisians who wanted Bibles and ministering to them. I just made sure to avoid Medenine during my travels, which had its challenges.

The weeks of travel after my Medenine incident brought me through many police checkpoints. I was stopped several times by officers and quickly released. One time, however, I was detained for a few hours and interrogated relentlessly. It was nighttime. I had been meeting with a Tunisian man who had requested a Bible. I sat with him at a cafe for several hours, talking about the Word of God and answering many of his questions. By the time I left his town, it was late and my presence as a foreigner driving alone in that part of Tunisia was highly suspicious. I was pulled over at an official police checkpoint and at least ten officers emptied the contents of my car. I was questioned — and questioned some more. Two of them ushered me inside the station and took me to a room upstairs where they continued to hammer me with questions and suspicions. They made copies of all of my paperwork. And then, just as I thought I would be arrested, or transferred, or kicked out of the country for spreading the gospel, they let me go. I returned to the island of Djerba that night, wondering about the many obstacles that stood in the way of gospel ministry in southern Tunisia and wishing I could somehow make the way easier for others coming after me.

Perhaps it is universal to want to find success in one’s endeavors. Achievement, after all, seems to be a sort of confirmation that education was not acquired for naught; hard work was not exerted meaninglessly; and time was not spent in vain. I do not presume to speak on behalf of all full-time Christian workers, but I do speak for myself when I say that there has been a frequent struggle in my mind over the years of what constitutes success in Christian ministry. My human nature wants to see measurable results — the kind of physical achievements that would grow a curriculum vitae; but New Testament success is far less physical and far more spiritual. Achieving New Testament success does require physical things like education (learning the Bible), hard work (serving God), and time, but the outcome is less likely to grow one’s curriculum vitae and more likely to grow one’s faith. New Testament success is God being glorified through spiritual growth in ourselves and others (for starters), initiated by our obedience to God and measured on an eternal scale. Closed doors and dead ends might just be part of the path that grows our faith and brings God glory.